Yet this technology isn’t four decades off. One Boston startup is working to make it a reality within the next five years. The delay, however, isn’t just technical — developers must also figure out how to assuage a squeamish public’s concerns around privacy.

Tracking online habits is nothing new. You are, for example, on Amazon browsing for alpaca pillows. Guess what you’re going to see advertised alongside your feed next time you’re on Facebook? Soft, fluffy alpaca pillows.

At first this was annoying — invasive, really. But slowly we all became used to it. Now we almost look forward to seeing our sought-after products being marketed to us, maybe even on sale. It’s connecting consumers directly with the products, as opposed to the old television model, which once forced us to sit through ShamWow commercials for no reason.

And that’s where online purchases had an edge over retailers. Until now.

Real Life Analytics, which launched its first beta test in an undisclosed Boston store, provides customer information through facial detection technology. Today it has the ability to identify eight different segments — child, adult, older adult, and senior (male and female for each). In the future, it’ll be able to determine size, beards, eyeglasses, collared shirts, and more. Today, this information tells retailers how much product of one kind to order and who shops in its stores. Down the road, it will likely be able to reveal so much more.

Today’s technology is not trying to figure out who you are — it’s merely trying to understand what segment you are. That will soon allow the retailer to customize an entire showroom for that type of individual. Think giant video walls that change for each customer — lighting, music, video — according to their profile. A young man with scruff and leather jacket might get loud music, images of scantily clothed women, and fast cars. An older woman with a scarf might seem to be walking into a tea room. All within the same space.

But whether this physical realm technology advances to the next step — identifying the customer, how much he or she earns, and a shopping history, for example — is still up in the air.

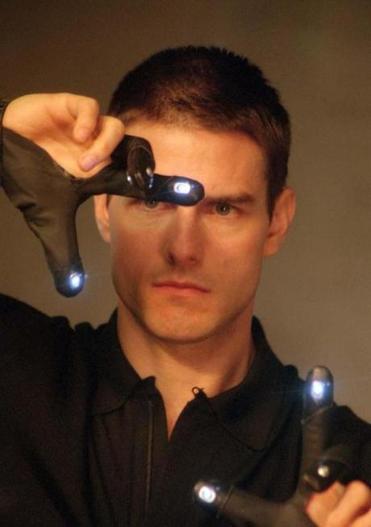

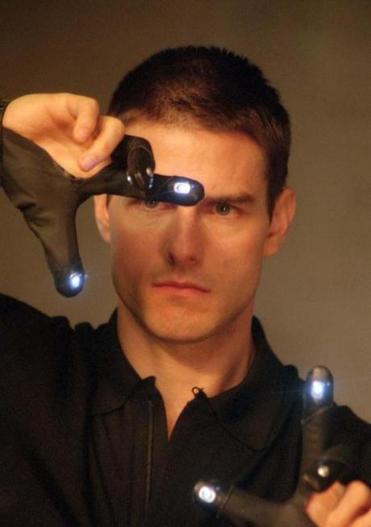

In the “Minority Report,” for instance, a retina-scanner ran an image against a database until it detected to whom the eye belonged. No such database exists presently. While today’s retailer can know if you have shopped there before — for example, a store can detect a unique string of numbers called a MAC address that emanates from your cell phone — it still doesn’t know who you are.

Today that information is protected by a firewall of sorts. That could easily change, however. Verizon could one day choose to make available its database of more than 125 million customers, allowing retailers to pair customer information with the once anonymous cell phone data. Or, Facebook, the gorilla in the room, with its 1.35 billion users, could do the same. All that’s needed is facial recognition software and faster processing for a store to determine who you are in real time.

Many years ago the corner grocer knew just about everything about his customers — much more than just what they purchased. Today the once anonymous Internet is closing in on just as cozy a relationship. And it seems that the computing public is slowly getting over their privacy concerns. For the average shopper, that might mean a deeper dive into our personal business, but it also means cheaper alpaca pillows.